Preface

This post is written in a ‘question and answer’ mode which was the style used in my recent book ‘How to talk to your robot dog’ and which investigated the possibility of developing Artificial Intelligence based on the canine intelligence. A key element of this particular story is the bond between dogs and humans.

QUESTION: Are there any topical insights into the relationship with dogs and humans that could relate to the persona of the ‘robot dog’?

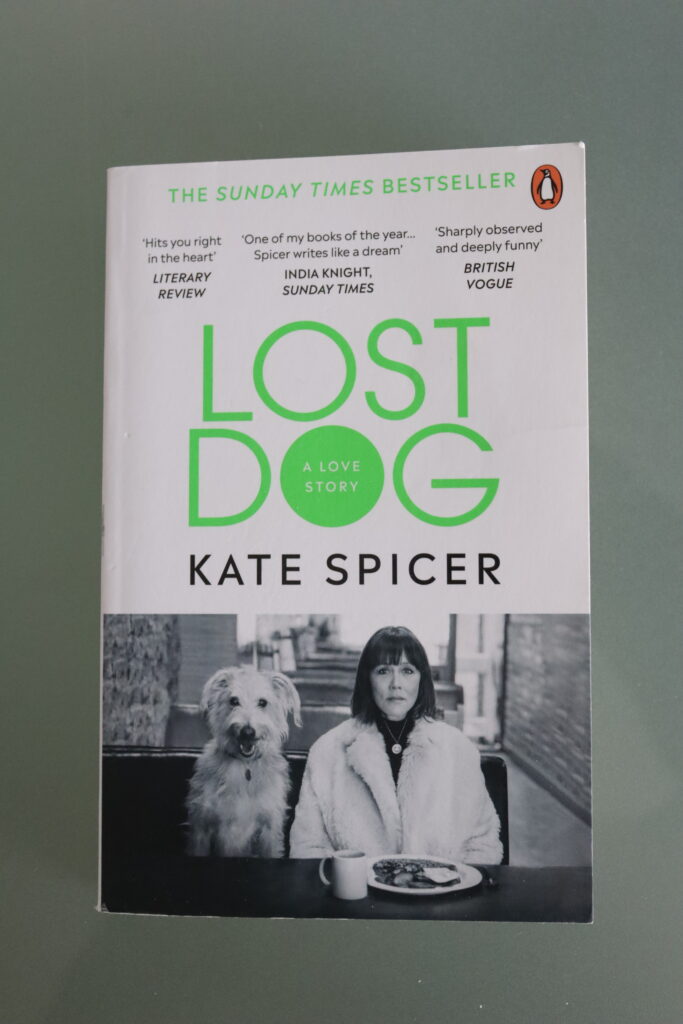

ANSWER: There are always books in print that relate to ‘special’ relationships between dogs and humans, in addition to the considerable number which have, through time, been published on this theme. This is an indication of the enduring popularity of dogs in human households. Often such accounts relate to dogs that have been expertly trained in specific skills, though various accounts can also describe how ‘ordinary’ dogs without any specialist training can impact significantly on human experience. The book ‘Lost Dog’ by the journalist Katie Spicer, for example, gives an account of how a rehomed dog called Wolfy (previous name Merlin) infused a measure of stability and direction into her lifestyle and relationships. This account details how looking after her new dog essentially rewires her social connections and places existing acquaintances into a new and revealing perspective. Instead of regarding life as an empty struggle, Katie begins to find value in her altered outlook and routines. An element of this would be the novel interaction with fellow dog owners. Behaviours would also be subject to influence. On walking past cafes, for example, a nudge from the lead would prompt her to call in for a snack that would of course be shared with Wolfy. The height of social engagements would in due course become ‘dog parties’ rather than social evenings among the glitterati of Notting Hill in London, where conversations would often lack substance and sincerity. The ‘before Wolfy’ and ‘after Wolfy’ episodes of her life are described in somewhat revealing detail in which the social inequalities of the capital city are exposed.

The depth of the psychological link between Katie and Wolfy was, however, starkly revealed when Wolfy went missing for a period of nine days, during which time Katie was struck down with painful feelings of loss, anxiety and separation. The stressful episode had taken place when Wolfy was being ‘minded’ by her brother while Katie and her partner attended a wedding. One of the positives from the trauma of initial loss of the dog was the considerable level of support among the London population to help her eventually find Wolfy. This level of assistance was largely among those of the ‘dog owning’ community, who were perhaps better placed to appreciate her predicament. Her book ‘Lost Dog’ is in some way a canvas on which the many variable characteristics of human nature are described and compared with the more favourable characteristics of canine behaviour. Some obvious characteristics of dogs which contrast with that of humans are that dogs do not display dishonest behaviour and once constructive relationships with humans are established, these are maintained.

Within the text of the book the author on occasion draws the reader’s attention to the hormone Oxytocin as some possible catalyst of the enduring relationship between humans and dogs. Early in her book Katie describes the effect of stroking the lurcher dog of a friend as ‘not much different from a dose of Valium’. This is perhaps an indication that her neural pathways were primed to be sensitive to such responses.

Oxytocin is a hormone secreted by the pituitary gland and its production can be stimulated in humans by a range of mechanisms which include childbirth, breast feeding, sex, ‘cuddling fellow humans’, ‘cuddling animals – especially dogs’, various forms of massage, eating and possibly the consuming of alcohol and the practice of smoking. This somewhat extensive list, however, may be somewhat incomplete and where it may be relevant to include the smelling of perfume, dressing up in best clothes and the appreciation of art. Oxytocin has often been termed the ‘cuddle hormone’ or the ‘love hormone’, though this may be to limit its scope of influence. The effect of Oxytocin on humans is, however, highly complex with interaction across diverse neural pathways in the brain and is considered to have potential impact across a wide range of ‘problem’ psychological conditions. The responses to Oxytocin are also likely to vary between individuals where there are components which reflect genetic characteristics. There is, however, an element of caution in identifying Oxytocin as a possible therapy for a range of cognitive and behavioral conditions. A key interaction of Oxytocin, however, is considered to be the release of Dopamine which provides a feeling of wellbeing. This mechanism in turn is considered to reinforce the activity which stimulated the pleasurable sensation. Thus ‘cuddling a dog’ can develop into an activity which becomes an everyday habit and which is probably reciprocated in the neural systems of the dog. This would imply that dogs also have the expectation of close human contact once it becomes established.

Studies in Oxytocin release have also shown that such responses are shared by both dogs and humans and where a significant mutual Oxytocin release in both parties can be detected with affectionate stroking and cuddling. It is also identified that eye contact with domestic dogs can stimulate a mutual release of Oxytocin. Thus a soulful stare between a dog and its owner initiated by a dog can be a deliberate ploy to maintain a bond with its owner. This could be a request for reassurance, a play session or a light snack.

It is an interesting observation that nursing mothers can report increased expressing of milk when affectionately stroking a dog – where the effect is triggered by the raising of Oxytocin levels. It is conjectured that over time the stimulation of Oxytocin in dogs through interaction with humans has developed during their period of domestication since such responses are found to be absent in wolves in the wild. Wild wolves would identify ‘eye gazing’ in this context as a challenge and threat. This could be considered as a ‘hijack’ by dogs of the mechanism to bond human to human relationships through mutual Oxytocin release. It is also likely that the action of Oxytocin has the effect of reinforcing memories of positive engagement with dogs, so that the sudden loss of a beloved pet stresses an emotional dependency that has been accentuated through the Oxytocin release mechanisms. Such effects would probably also be reflected in the trauma of breaking of human to human relationships.

In terms of the ‘depth’ of relationships between the ‘robot dog’ and its keeper, it is likely that the levels of bonding between humans and dogs based on mutual Oxytocin release cannot be expected to be directly replicated. By analogy, however, the persona of the ‘robot dog’ is designed to provide emotional and mental stimulation to its keeper which will encourage the keeper to ‘like’ the ‘robot dog’ and consequently pay it appropriate attention. This, however, is fertile ground for behavioural scientists to investigate Oxytocin responses of humans in relation to developments in Artificial Intelligence.