The Story Line

In one sense the Industrial Revolution was gathering steam – but not very efficiently. The Newcomen engine which initially was developed in 1712 was in use at numerous locations in Britain but was expensive to operate on account of the system’s poor conversion of input energy – coal – to useful power output. Perceptive engineers at this time were puzzling out how to improve the efficiency of Newcomen’s engine but without success. That is until a certain James Watt, then an instrument maker at Glasgow University, took a stroll on Glasgow Green on a Sunday morning in May 1765. It would be no surprise in those times that such a recreational stroll was being undertaken on a Sunday, the day on which no work of any formal nature was typically undertaken. By the end of his walk, Watt was able to link together in his mind all the elements of the radical design change required.

It was Watt’s inspiration to conceive of adding a condensing cylinder to the basic design of the steam engine and to have steam enter the active cylinder from opposite ends of the cylinder during the motion cycle. Watt had become all too familiar with the Newcomen engine after being requested to repair a model of the engine then in the possession of Glasgow University. In Newcomen’s steam engine steam from the boiler was allowed to expand a piston upwards to activate the beam engine. After a certain amount of travel the steam in the cylinder was condensed by a jet of cold water. This allowed atmospheric pressure on the upper side of the piston to push the piston down so that another cycle could be initiated. The overall process was inefficient since the active cylinder had to be heated from cold for each cycle and no heat from the steam in the active cylinder was recovered. A favourite means of demonstrating this effect is to pass steam into an empty steel container such as an oil drum, then close the steam line and inject a spray of cold water inside it. The steel shape immediately deforms as the pressure inside the vessel collapses. It would be some time later in 1769 after building various models to verify the improved design that Watt would file his famous patent. It is interesting to note that Glasgow University apparently made no effort to ‘cash in’ on Watt’s highly significant invention.

The improvement in efficiency of Watt’s design was striking. The amount of coal required for a given installation was reduced by a factor of between three and four and there was a ready uptake of the innovation. Watt would licence the technology for manufacturers to fabricate the components of each steam engine. This would reduce significantly the level of capital required to support the burgeoning enterprise. The income from an installation was based on the level of cost saving arising from the reduced level of coal use and so there would be income from an installation throughout its working life.

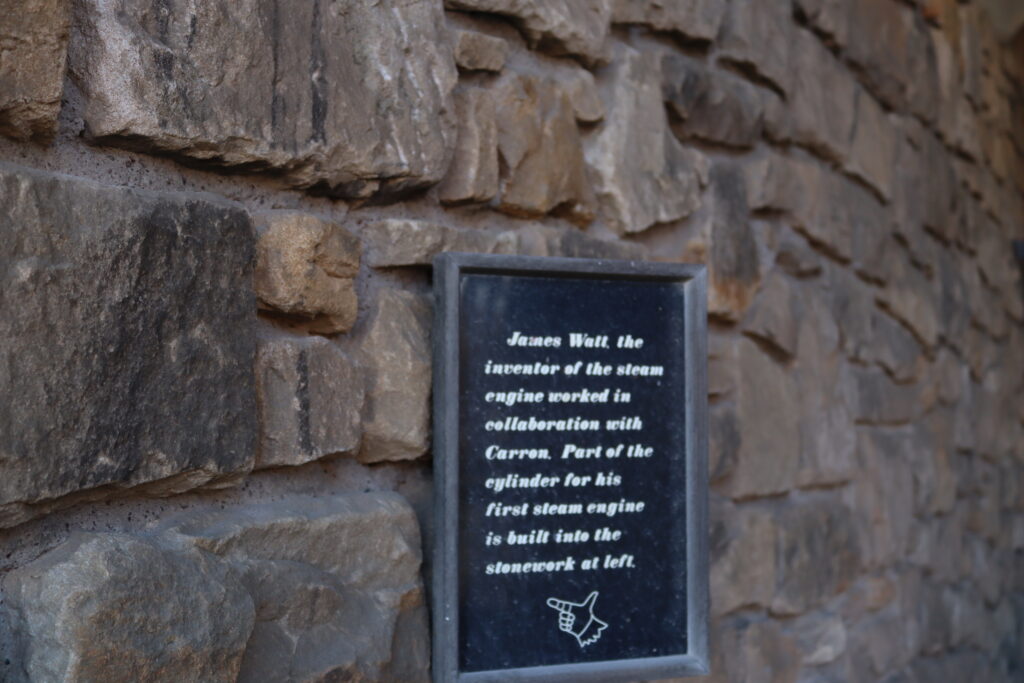

Watt would utilise available technologies in the manufacture of his first steam engine and used resources at the Carron Iron Foundry near Falkirk. Only the entrance tower – mistaken at my first sight for a church tower – of the extensive industrial site now survives. The discovery of the tower had been entirely accidental. I had been looking round the adjacent town of Larbert for landmarks of connection of family history. My interest in James Watt had, however, been triggered previously through visiting Sarehole Mill near Solihull, where Mathew Boulton, Watt’s later business partner in Birmingham had operated. On display in the tower are cannons thought to have been in use at the Battle of Waterloo. An initial impression of these is that they have been carefully scaled to provide the benefits of ease of deployment together with range and projectile effectiveness. A small plaque draws attention to a fragment of Watt’s original steam engine which is built into the wall of the tower with a date reference of 1766. You can reach up and touch it and in so doing acknowledge the start of the Industrial Revolution with James Watt.

Image Gallery