Life and Works

The various accounts of the Victorian photographer John Thompson (1837 – 1921) of his travels in the Far East, notably within China, reveal surprises on many levels. These can be considered to include the then legacy of China’s past, the then contradictory nature of its observed present and insights into what it may become in a more hopeful future. Underlying these journals, however, is a constant theme of the desperate social conditions experienced by the majority of its inhabitants. The series of surviving images from his extensive picture library provide a valuable insight into life in the Far East and where various narratives of his travels add light and colour to their black and white lines. A key observation made was that the low cost of skilled artisan labour allowed the prolific manufacture of many ranges of craft goods such as silks and pottery.

There are also references to obscure treaties such as the Treaty of Shimonosaki of 1895 which may yet rattle the swords of future conflicts. The Treaty essentially confirmed renouncement by China to influence within the Korean territories and ceded Formosa to Japan. In addition, various concession of access to Chinese territories were also granted in favour of Japan. Events subsequent to the treaty, as recounted by Thompson, enabled the use of land by Russia to secure an ice free port on the Pacific Ocean. Thompson correctly surmised that in the fullness of time the concession to operate a railway across Chinese territory will become a more permanent arrangement of territorial consolidation.

A key observation by Thompson of the various failings of Imperial China was the pervasive levels of corruption which prevented central authority from effectively engaging in the proper duties of government. The sharp observations of Thompson outline a series of remedies to bring order out of chaos and where principally these relate to the proper collection and utilisation of tax revenues. Funds were, for example, made available centrally to the regional governors for the establishment and maintenance of a standing army but in fact there was no evidence of the existence of such an army. The Imperial system of government as observed by Thompson still was based on the system of award of government posts based on an examination system surviving from antiquity. In theory the most lowly could rise to the most high, though this was highly unlikely without the advantages of access to an elite educational system.

Some of John Thompson’s most hazardous travels were within the island kingdom known then as Formosa but of course more familiar to us today as Taiwan. Under the guidance of a knowledgeable missionary, careful photographic record was obtained of the dangerous inland regions peopled by tribes who acted as intermediaries between the wild mountain tribespeople and the colonising Chinese. It is a sombre reflection, however, to surmise the fate of the native peoples of the island as described in Thompson’s detailed narrative. Likewise, the dense luxuriant forests are probably also now a distant memory. Thompson recounts the ceding of Formosa to the Japanese as a potential turning of the tide for advancement of progressive Western methodology in the Orient. Little did he know the reign of terror that would unfold as part of Japan’s imperial ambitions unchecked by any consideration of rights of individuals and nations. Formosa would return to Chinese ownership at the end if World War II and later become a refuge for defeated nationalist forces in conflict with the communist Peoples Liberation Army. During his travels within Formosa, however, a key focus was the photographic recording of his travels through the often dangerous hinterland and where it was often a challenge to maintain the effectiveness of the collodion photographic method that he employed. A key process relating to this was to use heat to evaporate alcohol from a solution containing silver nitrate.

Thompson was also a keen observer of the inherent industry of the Chinese population where often in the most challenging work conditions and using what would appear inappropriate work tools and equipment, goods of unsurpassed quality could be produced. A noted example of this related to the weaving of silk where the most complex of designs and patterns could be expertly manufactured. Thompson very aptly anticipates the ability of China to eclipse European manufacturers in the production of all manner of fabrics should methods of more highly mechanised production be embraced. Thompson would in fact have an opportunity to observe the beginnings of this process based on various mechanised weaving mills established in Shanghai.

Thompson describes in some detail elements of the tea industry in China at a time when the exports of this commodity were beginning to be challenged by tea production from India and Ceylon under British rule. While teas of the finest quality were still being produced in China, there were perhaps more variables in the complex processes of production and delivery to contend with and trade in this commodity was regarded as a more high risk venture. Thompson describes the mechanisms of how a merchant would purchase teas from a tea warehouse, where specific boxes of tea would be selected at random and tea produced from each consignment and sampled in a tasting room with a north facing window to give a constant quality of light illumination to gauge the colour of the various infusions. If all proved satisfactory a consignment would be ordered and the transaction duly processed. Thompson was aware of instances of outright deception regarding the quality and origin of exported teas where processes were known where used teas were collected dried and mixed with various substances to give a totally false impression of its quality. Issues also arose regarding Chinese teas in shipping the considerable distance to the European markets where it was not uncommon for significant deterioration of product quality to occur during the long sea journey. Thompson refers also to the stimulus to World trade with the opening of the Suez Canal in 1869 and which reduced the voyage distance between China and Europe by some 3500 nautical miles.

The travels of John Thomson in the Far East are legendary, where often in China he would venture to localities that had not previously set eyes on foreigners. A particular notable achievement was navigation up the treacherous gorges of the Yangtze river which in his writings is recounted in entertaining narrative detail and with the bonus of extensive photographic record of the adventure. In total the outward and return journeys would amount to around 1500 miles. Thompson is in particular adept at describing the particular behaviours and mannerisms of the individuals encountered in his travels, and the questionable characters of the boat crew for the Yangtze trip are described in somewhat alarming detail. The journals of John Thompson embrace so much of the history of China that their study would certainly enrich present day understanding of Chinese affairs. During his travels, there were various reminders of extreme events that had shaken the kingdom profoundly.

The Taiping Rebellion had in particular been one commented on by Thompson and was the conflict between the Manchu-led Qing dynasty and the Han, Hakka-led Taiping Heavenly Kingdom whose figurehead was Hong Xiuquan, an ethnic Hakka and the self-proclaimed brother of Jesus Christ. The scale of deaths was a par with that of the first World War and significantly weakened the central state administration though these effects would become more apparent in years subsequent to Thompson’s narratives. The current overdrive of Communist China to root out any diverse opinions within its territories is perhaps in some way linked to historical memories of contrary ideologies, though with proper insight such ruthlessness can itself be identified as a destabilising factor. The then senior ruling officials that Thompson was able to converse with were, however, confident that China would in due course make the transition from an archaic feudal empire to a modern ‘westernised’ state and that as a process once begun, the process would happen quickly.

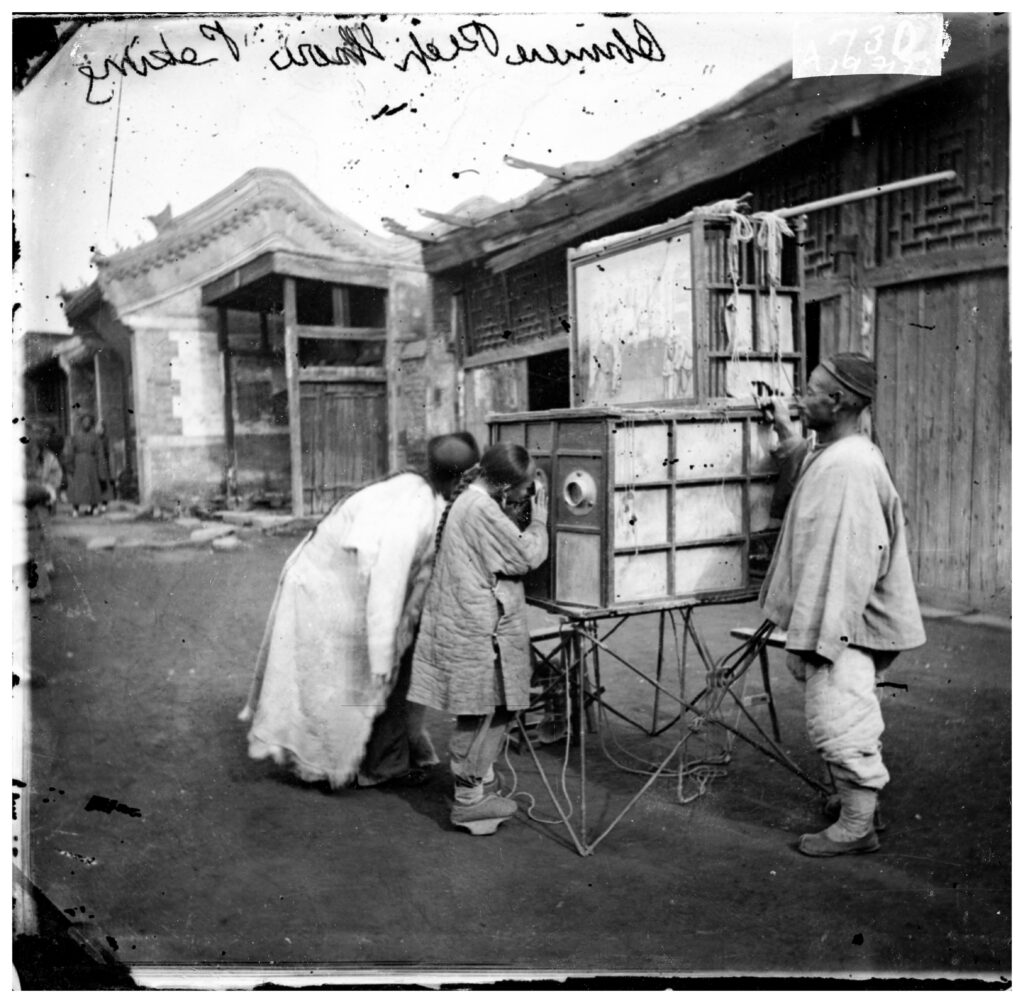

Perhaps the most striking account of things seen in China by Thompson was the description of the crowded streets of Peking, with every commodity and service under the sun available on the bustling thoroughfares. Typically the centre of such highways provided passage for carts taking goods into and out of the metropolis. Goods from all manner of shops would spill out onto the wide pavement. On the occasion of use of such highways by the Emperor, the confusion of human activity would be cleared away so as not to offend the Royal gaze. It was probably also a prudent security precaution. Thompson was, as ever, mindful of the need to create a photographic record of his observations and various images of such street life were preserved for posterity. Thompson notes with some amusement a pavement ‘peep show’ which he maintains would not be tolerated in his native Edinburgh. In a way what Thompson is observing is the demonstration of a model of highly complex economic activity whereby a large population sustains itself by trading in a vast array of goods and services and where the gains derived from such individual transactions range from the significant to the almost negligible.

It is also obvious that Thompson was a competent Chinese linguist and was also adept at reading the written language. These skills proved invaluable in the planning and resourcing of expeditions into the Chinese hinterland and negotiating the many challenges thus encountered. Thompson was also aware of the risks that foreigners were exposed to in the remote Chinese hinterland as witnessed in the ruins of the French Roman Catholic Cathedral and convent at Tienjin which in 1870 had been attacked by a mob of locals and up to 60 individuals killed. These locals had believed the vile propaganda that Westerners used the eyes of Chinese children as a medical remedy. Dire conspiracy theories, it would seem, are by no means a new invention. Historians today, however, identify additional factors which precipitated such horrific events.

It is a relevant reflection to consider using the emergent technology of applying colour to such historical black and white images, as if to introduce even more vitality and resonance into them. Such technology was, for example, used to significant effect by Peter Jackson, the famous film director, for black and white images of the Great War. A comparable project applied to Thompson’s photographic collection, however, would require the collective skills of the very best of relevant professionals and where key resources for faithful coloration of specific artifacts would be held in the world’s premier museums. A key player in this project would, of course, be modern China, for access to relevant material. Such a project could of course attract the attention of the Wellcome Collection based in London and which curates a significant number of Thompson’s images of the Far East. Subject to the terms of applicable image use, such images are free to download, in marked contrast to the confounding bureaucracy of museums and galleries, which invariably act to deter access. In terms of applying colour to black and white images, however, an array of affordable professional image processing tools are available for such tasks. It could even be a revealing exercise to follow in the Thompson’s footsteps to revisit certain of the landmark features he initially captured. This would be an exercise in both reflection of a transformed society and a means of providing information for faithful image restoration.

Examples of Photographs

An extensive series of photographs of John Thompson are preserved in the Wellcome Collection – and where an extensive series of ‘contact prints’ have been derived from the original ‘Silver Nitrate’ negatives. A small set of these are included here. Often additional details of individual images are often included in the ‘Collection’ reference.

China: a Manchu bride. Photograph, 1981, from a negative by John Thomson, 1871. Credit: Wellcome Collection. Attribution 4.0 International (CC BY 4.0)

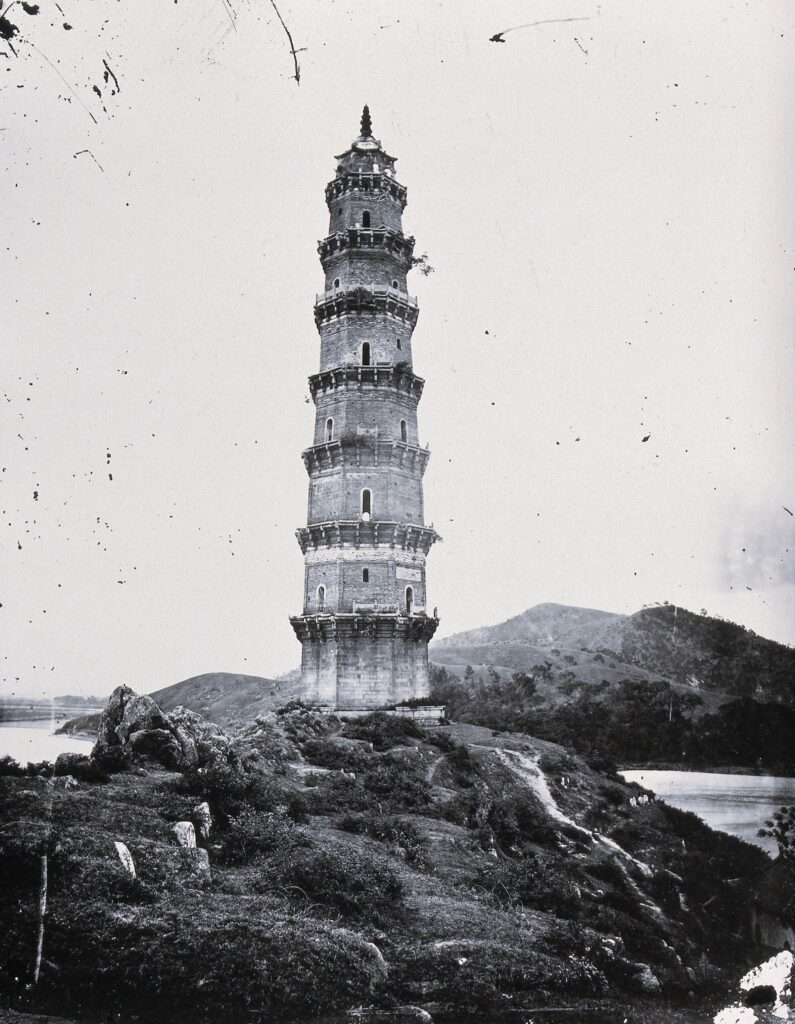

Kwangtung province, China. Photograph by John Thomson, 1870. Credit: Wellcome Collection. Public Domain Mark

Peking, Pechili province, China: a magic lantern show. Photograph by John Thomson, 1869. Credit: Wellcome Collection. Public Domain Mark