Most of the time we have relatively little interest in the origins of our national anthem and even less in that of other nations – except perhaps when they may have better tunes. The national anthem of America – the ‘Star-Spangled Banner’ has, however, some strands of mutual interest for both the Americans and the British since its roots go back to the war between these two countries which began in 1812. Britain had been drawn into a war against America after the latter’s invasion of Canada. After removing the invaders from Canadian soil, the British proceeded to launch an offensive against American territory – partly as a retaliation against American actions and partly to seize chunks of territory for the Crown. The acts of destruction carried out by the British in the city of Washington were possible due to weak defending American forces though other targets including New York, Baltimore and New Orleans were able to be defended more successfully by the Americans.

The action in Baltimore was witnessed by a certain Francis Scott Key while detained on board a British ship and who was seeking the release of a certain Dr William Beanes who had previously been detained in Washington. Key was able to observe the bombardment of Fort McHenry by British warships which began on September 13th 1814 and carried on till the morning of the next day. A British force had also landed with the aim of defeating local American forces but eventually withdrew, in line with orders, when it was assessed that the defending forces were stronger than anticipated. Key made some notes of his observations of the failure of the British attack on the Fort as signalled by the continued flying of the large garrison flag. He completed lines of poetry recording his observations a few days later. A friend suggested a title of ‘The Defence of Fort McHenry’. The famous first verse as now used is as follows:-

O say can you see, by the dawn’s early light,

What so proudly we hail’d at the twilight’s last gleaming,

Whose broad stripes and bright stars through the perilous fight

O’er the ramparts we watch’d were so gallantly streaming?

And the rocket’s red glare, the bombs bursting in air,

Gave proof through the night that our flag was still there,

O say does that star-spangled banner yet wave

O’er the land of the free and the home of the brave?”

It was not until 1931, however, that the anthem was officially adopted as American National Anthem. The officer in command of Fort McHenry at the time of its attack had been a certain George Armistead who had in fact deliberately organised the making of the large garrison flag so that it would be ‘a flag so large that the British would have no difficulty seeing it from a distance’. Although no significant damage was done to the fort, the stress of the preparations and the fearsome bombardment severely damaged the health of Amistead who died some three years later at the age of 38.

As a point of wondering, what was to become of the large garrison flag at Fort McHenry? Fortunately the flag, as a cherished emblem of American pride, has been carefully preserved and is on display at the National Museum of American History in Washington. For quite a period of time, however, the flag had remained in the ‘safe keeping’ of family members. The flag itself was constructed on a large scale with an original size some 30 by 42 feet (9.1 by 12.8 metres) and was deliberately created to clearly demonstrate the American will to prevail. The flag originally contained 15 stars and 15 stripes as was the system in 1814 to record the then 15 states in the Union.

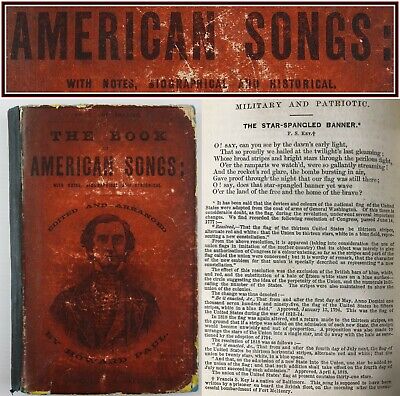

It is relevant to relate that these details came to light from a chance view of the on-line bookshop of Gill Ferguson’s bookshop at Skeabost on the Isle of Skye – where the insert of interest is shown below.