The 400th anniversary of the publication of Shakespeare’s first folio has been marked in various ways wherever such volumes exist. This typically has carried a celebratory tone, by way of remembering a notable work as Ben Johnson confirmed in his dedication in the first folio that the Bard’s work was ‘for all ages’.

Around 50 copies exist of the first folio within the United Kingdom and a relatively accessible copy at Mount Stuart on the Isle of Bute in Scotland provides its own unique history of entwined provenance and conservation. In particular, this first folio together with other subsequent folio editions has been open to private viewing sessions during 2023 under the watchful eye of collection specialists.

The Crichton Stuart family had an avid interest in Shakespeare folio editions succeeded in obtaining a first folio by 1896 through the efforts of the Third Marquess of Bute. This particular copy is thought to have been in the possession until 1807 of a certain Shakespearean scholar Isaac Reed who acquired the work in 1786 from the widow of the Shakespearean actor, John Henderson. On the page in the first folio describing the names of the ‘principal actors’, the entry ‘Thomas Nicholls 1755’ appears although efforts to trace this individual have so far not proved successful.

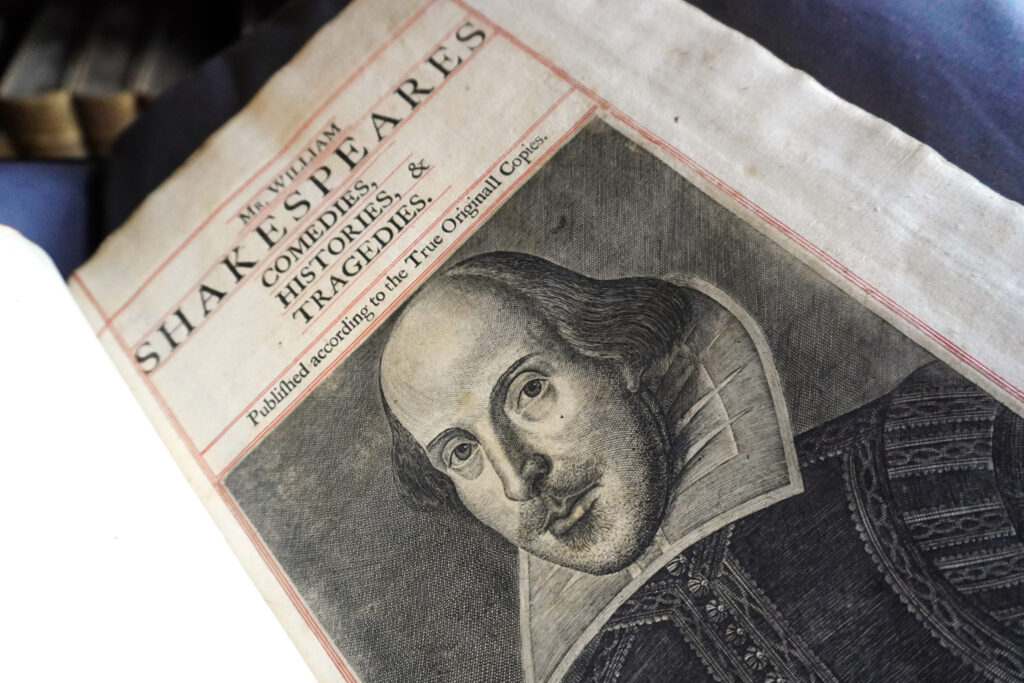

The famous frontispiece of the likeness of Shakespeare by Martin Droeshout is perhaps the most recognised feature of the first folio.

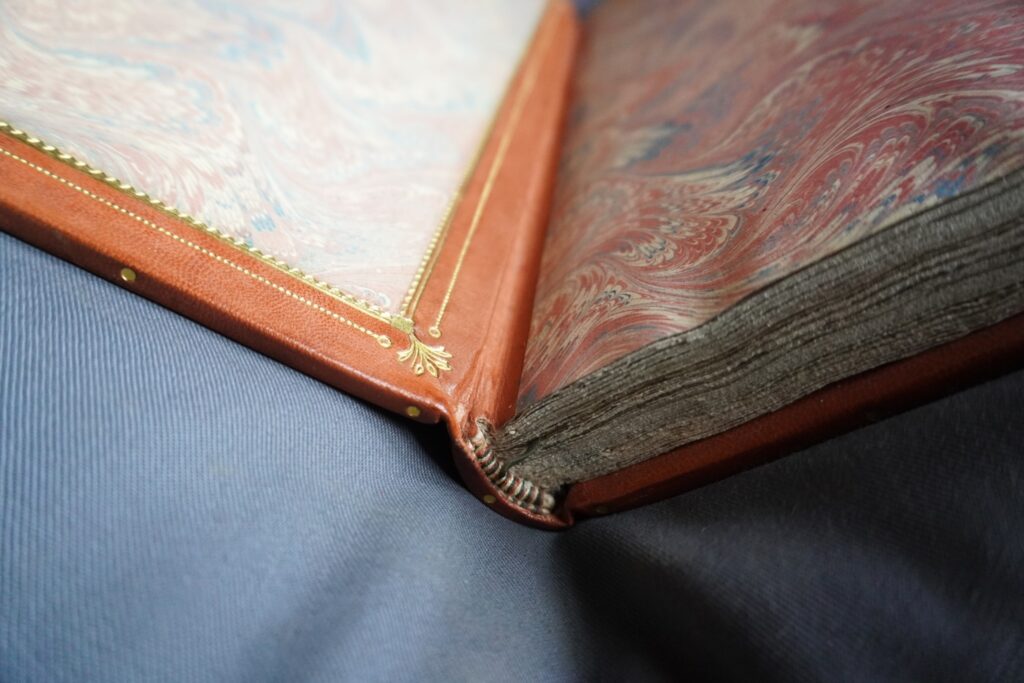

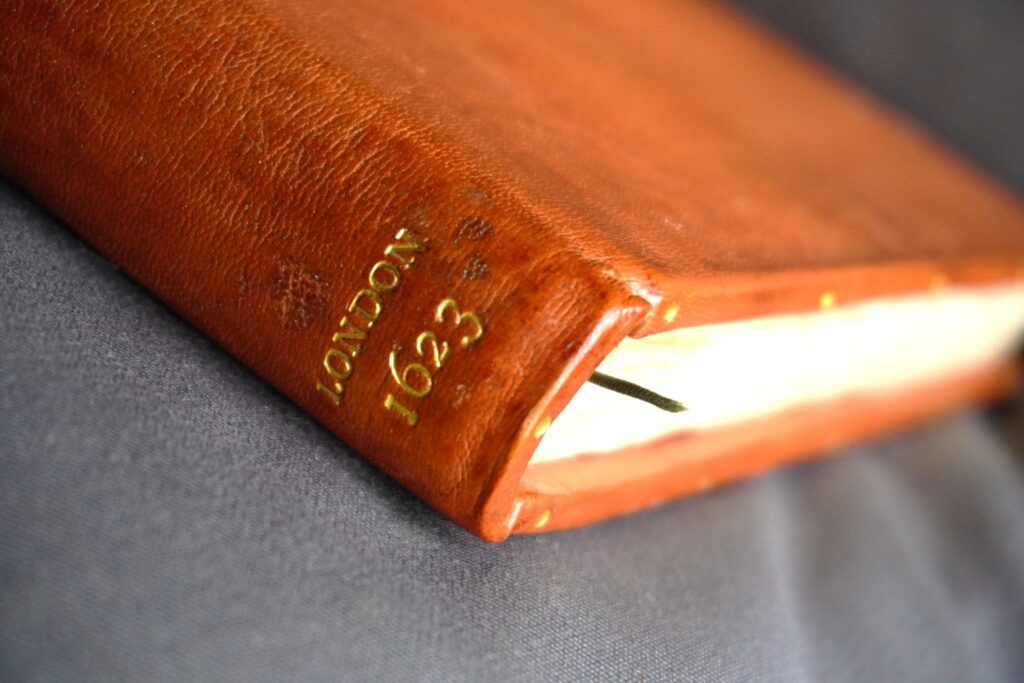

This first folio was rebound in its existing format as three separate volumes around 1931 by William Pender, a noted London bookbinder. As part of this restorative process, the page margins of the original folio were trimmed and inserted within a ‘window’ of new paper of uniform size. This was undertaken probably due to the condition of the work which may have had marked or torn paper margins. This would represent a considerable labour by the bookbinder. While this better preserves the valuable edition, marks of annotation or comment in the original page margins would have been lost.

Following the outbreak of the Second World War, the books belonging to the then Fourth Marquess in London were moved to Scotland for safe keeping and the First Folio was lodged in the Blue Library at Mount Stuart on the Isle of Bute where it has subsequently remained.

The contents of the folio, however, are otherwise entirely present such as the watermarks in the paper which was probably produced from rag waste, creating a diverse chemical provenance in the fabric of the paper from all sorts of ‘organic’ sources. Parallel lines can be seen running top to bottom when a light is shone from behind a page – by way of a ubiquitous mobile phone. This is likely to have originated as part of the paper making process when the paper slurry was poured into a receptacle to drain and form a length of wet paper that would have been subsequently hung out to dry. The occasional watermark blob on the paper is likely have been the result of water dripping onto the paper surface during the various stages of its production. The faint impression of print from the opposite side of each page is clearly visible.

The metal used to cast the type would have been lead, though on the continent other superior alloys of superior robustness were coming into use. Presumably individual letters were cast from moulds and which would have been a skill in itself. Also, at some stage, an artisan would have carved the mould of a given letter of specific font and size. How many letters were able to be cast from a given mould?

It is interesting to reflect that various stages of production of the first folio were matched to the skills of various individuals within various guilds. In a busy print shop did the trays of type all age together based on daily usage or was there a set of best type and a set of reduced quality of even one of ‘chancing it’ quality?

In an age when where was a great emphasis on specific skills, the differentiation of skills in the print workshop would have been jealously guarded. The apprentices of various trades in London around that time often engaged in unruly mob behaviour against anything that met their displeasure – such as the ‘strangers’ from foreign shores such as Huguenot refugees fleeing for their lives from France. These issues would have been known to Shakespeare when he lodged for a time with the Mountjoy family in Silver Street in London. (See ‘The Lodger’ by Charles Nicholl).

On browsing through a particular volume of the First Folio, gazing on the front page of The Tempest, for example, the mind draws up a host of questions, such is the power of its presence. When viewing the last page of the Tempest, it is possible to read text using a mirror of the print on the opposite side of the page from ‘Two Gentlemen of Verona’ (a shepherd seeks the sheep….).

Thus gaze and be amazed but gaze and also be more than subtly intrigued. An encounter with a first folio is surely more than an observation of its printed pages.